Rare Disease Awareness Month

February is a month of many things. It’s Black History Month, a time to recognize the incredible contributions of African Americans, including pioneers in health and medicine. It’s also the month we celebrate Presidents’ Day and Valentine’s Day.

And, it’s Rare Disease Month.

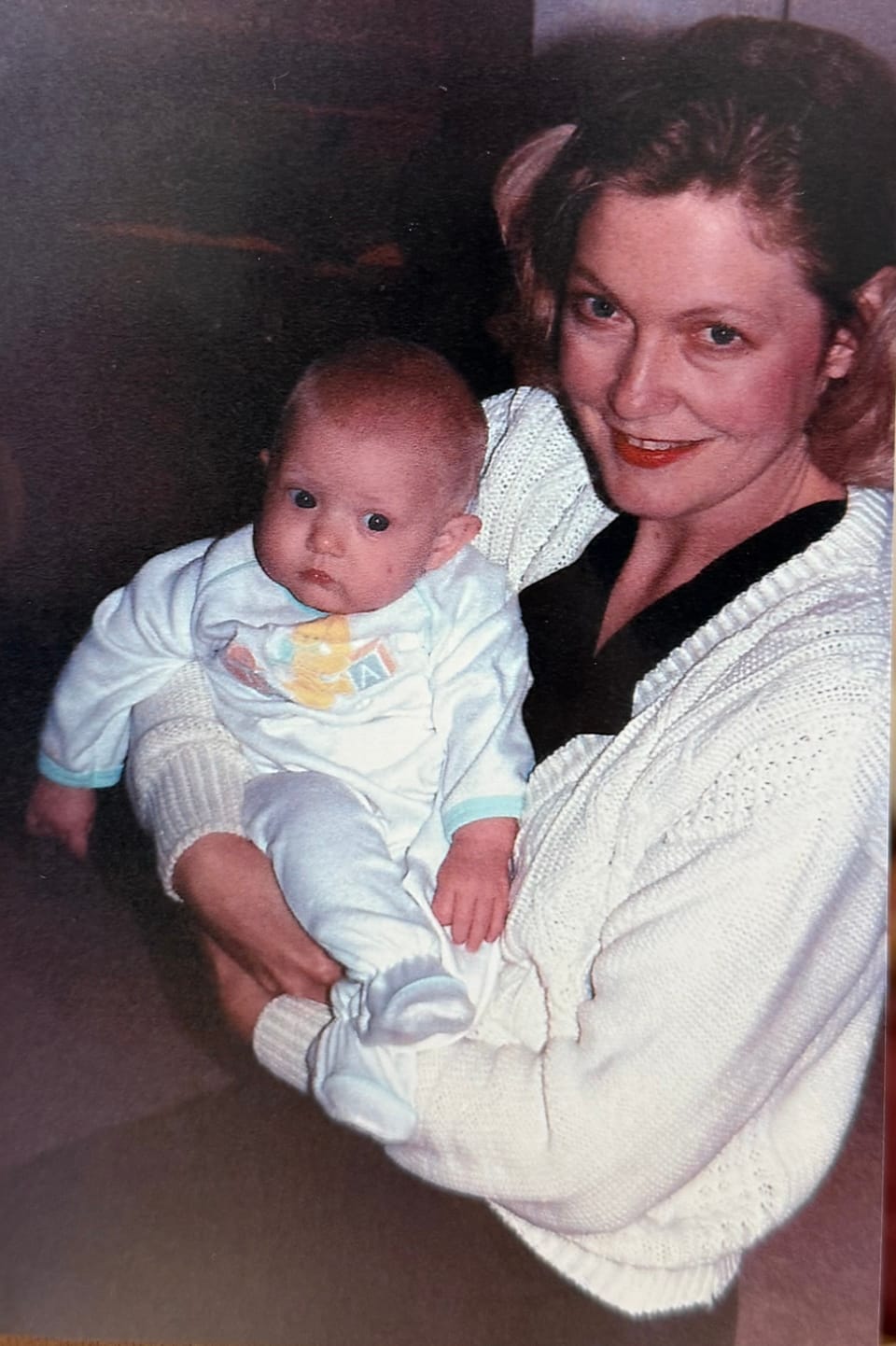

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Now say that three times fast. Just kidding—don’t worry, I can’t even say it once, slowly. This rare lung disease has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. While I am a member of the Chronic Illness Club, I am not a Lammie (a person diagnosed with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis, or LAM). My mom, Marie, was.

Throughout my childhood, I always saw her with a nasal cannula and her oxygen tank by her side. We called the portable ones “baby” because if they tipped over, they would let out a high-pitched “cry” as the pressure released. I only remember a few times when she didn’t need oxygen—those were after her lung transplant in the mid-to-late ‘90s. One time, feeling adventurous, she took us to a roller rink. She fell and broke her wrist (or maybe her arm—I can’t remember exactly). She found it funny in an ironic way. She always had a great sense of humor.

Growing up with a mom who had a rare disease didn’t feel all that different from having a mom in perfect health. Yes, she was on oxygen, but she still showed up—at Girl Scout meetings, school plays, soccer games. She took me to musicals, hung out with me and my friends, and was just there. The real differences were subtle: being extra careful when someone was sick, the times she was hospitalized and I had to stay with family or friends, and her heartbreaking realization that she could no longer eat grapefruit after her transplant.

But not everyone saw my mom the way I did. As a child, I heard the hurtful words of other parents and kids. I once asked a girl if she could come to a sleepover with a few other friends, and her mom loudly declared in front of everyone, “No, you can’t spend the night. Her mom can’t parent y’all because she has a disease.” I was furious. My mom had never let her illness affect her ability to care for me, my friends, or anyone else. She was an incredible mom.

Another time, an ambulance sped past our school with its lights on, and I burst into tears. My mom had been sick, and as an anxious preteen, I was terrified that something had happened to her. A girl in the lunch line turned around and sneered, “I hope it’s going to your house. I hope your mom died.” I completely lost my composure. The next thing I knew, we were both in the principal’s office. I never understood how people could be so cruel—so judgmental when they were only peeking in from the outside.

I remember sitting at the kitchen table playing rummy while she sorted medications, checked her oxygen levels, and did breathing tests. She’d let me try the breathing test—a device where you had to blow air to keep a little ball hovering. She’d tell me about the medications she was taking, and we’d laugh about the one that smelled exactly like a skunk.

She loved sitting in the backyard with our dogs, throwing them tennis balls and blowing bubbles for them to chase. As a kid, I didn’t understand how much effort those everyday activities took. As an adult, I do—because while I don’t have LAM, I do manage multiple chronic illnesses.

As I’ve grown, I’ve connected with many people navigating rare diseases and chronic illnesses. I’ve had the opportunity to volunteer with The LAM Foundation, join Chronic Boss Collective (a community supporting individuals with chronic illnesses), and become an affiliate with Rare Patient Voices, which helps patients and caregivers participate in research studies. I’ve even consulted on the development of Connectome, an app designed for tracking and managing chronic conditions.

Healthcare, diagnoses, treatments—these things can feel overwhelming, especially when you don’t feel like you have a community. Sometimes, a doctor will say something like, “We’re going to keep an eye on ___,” and suddenly, you’re stuck in limbo, feeling uncertain, confused, and alone. For example, my doctors monitor my bloodwork for antiphospholipid antibodies. I go through test after test, scan after scan, just to make sure I don’t have any blood clots. Then I wait. It’s been over two years of watching and waiting. At this point, it’s not if—it’s when.

I know so many others are in the same position—whether it was my mom, waiting for a lung transplant, or people today, waiting for a diagnosis, a treatment, a cure.

So, if you need someone to advocate for you, I’m here. We all deserve better when it comes to our health. We are all navigating a broken system, piecing things together the best we can—finding the right doctors, asking the right questions, fighting for what we need. Life is already hard enough without adding the complications of healthcare.

If you take one thing from this, I hope it’s this: Consider becoming an organ donor.

When you pass away, your organs won’t be of any use to you—but they could give someone else years of life. Someone like my mom, who was given just six months to live but was blessed with four more years thanks to a young man who chose to be an organ donor. Signing up takes just a few clicks or a simple checkmark when renewing your license.

If you’re open to it, join NMDP, the National Marrow Donor Program (formerly Be the Match). This program connects marrow donors with patients in need of life-saving transplants.

And if you’re able, donate blood. If you’re in Austin, where I used to live, I highly recommend We Are Blood. If you’re elsewhere, AABB can help you find a donation center near you.

This wrote was written in honor of my mom, Marie.

June 30th, 1956 - February 14th, 2002.

I hope this post inspires you—whether to take a step toward supporting your own health or to help someone else in their journey.

Member discussion